Pacific Sea Nettle

Chrysaora fuscescens

Look but don’t touch! As one can infer from the species’ name, the sting of a Pacific sea nettle can be just as impressive as its vibrant colours. While their stings are rarely dangerous, many sea-going naturalists (underwater photographers in particular) often pay the price for a close encounter with these magnificent animals, myself included.

The Pacific sea nettle is one of the most well recognized jellies globally, featured front-and-centre at aquariums and ocean learning centres around the world. Like many famous marine species such as the Giant Pacific octopus, Wolf eel, and Pacific spiny lumpsucker, this jelly is right at home here in the Pacific Northwest and can be found in many regions without too much difficulty.

This artwork is inspired by my photo of a Pacific sea nettle below. This individual was the 2nd Pacific sea nettle I had ever seen in the wild:

November 2017: A small Pacific sea nettle bobs along the surface in a bay close to East Sooke Park in Sooke, B.C. By photographing the animal from below, it almost looks like it is floating through the sky.

📖 Description 📖

The Pacific sea nettle is one of the largest jellies in the world. Growing up to 30cm across, with tentacles trailing for up to 3m behind, It is only 2nd in size behind the truly enormous Lions’ mane jelly (at least in the Northeast Pacific) [1] [2]. Like many of the larger jelly species found locally, the Pacific sea nettle is a voracious predator with an all-inclusive diet. Nearly any small creature unfortunate to make contact with any of its stinging tentacles will be captured and consumed.

Like most jellies, the frilly, white oral arms of the Pacific sea nettle trails behind the animal much like the tentacles. Once tentacles ensnare prey, it is passed to the oral arms which slowly carry it towards the mouth located on the underside of the jelly’s bell (the round, top part of the jelly).

Like most jellies (but not all!), Sea nettles do not have eyes like us, however they have a ring of interesting organs located around the edge of the bell. These organs are known as rhopalia, and are capable of sensing light and dark as well as the animal’s orientation in the water.

November 2017: An Adult sea nettle patrols a shallow bay, in search of scraps left over from a recent plankton bloom. Photographed near Albert Head Lagoon in Esquimalt, B.C.

🌎 Distribution 🌎

As previously mentioned, The Pacific sea nettle is local to the Pacific Northwest. found anywhere between Arctic Alaska and Southern California [3]. While the species has a broad distribution, they are generally found in open ocean environments, and are less-often seen in sheltered regions such as the Salish sea and Barkley sound. However ocean currents can carry Pacific sea nettles into these areas on occasion.

Distribution of the Pacific sea nettle, Chrysaora fuscescens. Suitable habitat depicted in red.

🏝 Habitat 🏝

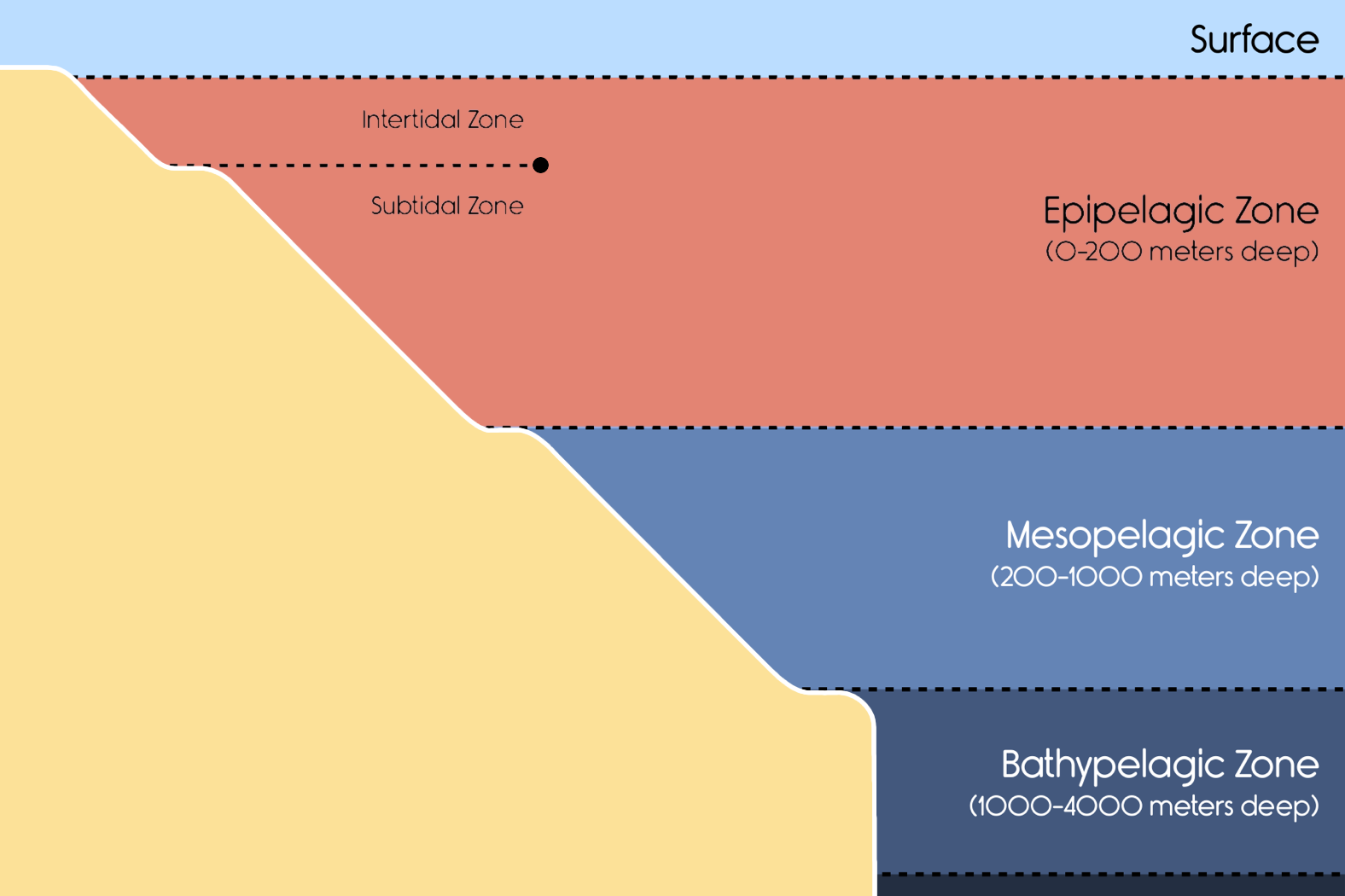

Being such fragile animals, Sea nettles prefer the open ocean in areas where there is little risk of collision with rocky reefs or entanglement with seaweeds. Sea nettles are most often encountered close to the surface of the sea, as this is typically where the greatest concentration of plankton is. There are documented observations of this species as far deep as 200m below the surface [4].

Depth of suitable habitat for the Pacific sea nettle, Chrysaora fuscescens. Suitable habitat depicted in red. Not to scale.

Interestingly, Pacific sea nettles occur in enormous numbers off the coast of Oregon, a phenomenon which has been of particular interest to biologists and conservationists. In this region, there is an ocean dead zone where concentrations of oxygen in the water are dangerously low for most species. Jellies, consisting of up to 98% water, need far less oxygen than most animals and appear to thrive in these conditions. The dead zone itself first appeared in 2002, and is thought to be caused by a combination of climate change and human activity in the region.

🌊 Diet 🌊

Sea nettles will consume anything that it is capable of subduing with its tentacles. This will include microscopic creatures such as copepods, larval fish, and larval invertebrates, but also large animals such as salps and other jellies. In turn, Sea nettles are eaten by large fishes such as the Ocean sunfish, Sea turtles such as the Leatherback sea turtle, as well as some species of seabirds [1].

November 2017: A sea nettle in rather poor condition that has inadvertently made its way into a kelp forest. By mid-November, food becomes scarce as many species begin entering a period of ‘dormancy’, which has potentially led this sea nettle into this habitat in search of food.

🌿 Life Cycle 🌿

The lifecycle of the jellies is very complex and often confusing. What we know and love as a jelly, is in fact only half of their lifecycle. Jellies undergo what is called alternation of generations. The two components of the jelly lifecycle consist of the medusa (which reproduces sexually), and the polyp (which reproduces asexually).

The medusa stage is what we know as a jelly. Jellies are either male or female, and reproduce by releasing eggs and sperm into the surrounding water. Fertilized eggs float around and develop into what is called a planular larva. This creature searches for a suitable location on the sea floor to develop into a polyp.

The polyp initially resembles a tiny sea anemone, and is not male or female. Over time, this polyp begins cloning a stack of upside down, baby medusae. These baby jellies eventually pop off and swim upwards into the water column to begin their lives as what we again, know as jellies [1].

February 2020: A very large sea nettle, one of hundreds in the middle of what appeared to be a migration sweeping past Point Piños in Monterey, B.C.

📚 References 📚

[1] Aquarium of the Pacific, (n.d.). Pacific sea nettle. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/pacific_sea_nettles

[2] McClain, Craig, R., et al. (2015). Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ. 3: e715. 10.7717/peerj.715

[3] World Register of Marine Species. (n.d.). Chrysaora fuscescens (Brandt, 1835). Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=287206

[4] Gershwin, L. (2008). Systematics and biogeography of the jellyfish Chrysaora colorata and C. achylos (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 88(1):83-88.