Black-eyed Hermit Crab

Pagurus armatus

‘Adorable’ might not be the first word you use to describe a creature that scavenges the sea floor while living in the remains of another animal, but that soon changes once you have met the Black-eyed hermit crab.

On a personal note, this is my absolute favourite species. It had taken me some time to choose between the Black-eyed hermit crab, Pacific spiny lumpsucker, & the Puget sound king crab, but I simply cannot resist those curious, beady little black eyes. While working with these hermits, I have found them to be gentle, friendly, and quite possibly capable of learning.

This artwork is inspired by my photograph of the Black-eyed hermit crab below:

September 2017: A Black-eyed hermit crab peers out from underneath its shell off of Clover Point, Victoria, B.C.

📖 Description 📖

The Black-eyed hermit crab is the largest hermit crab local to the Pacific Northwest, and may even be one of the largest non-terrestrial hermit crabs worldwide [1].

Like almost all hermit crabs, Black-eyed hermits require empty shells to live in. Unlike most of their body, their tails do not have a hard shell and are quite vulnerable to threats. As they do grow quite large, they require larger and larger shells to live in as they grow older. After a certain size, there is only one shell available in the Pacific Northwest that they fit into.

This is of course, the shell of the Lewis’ moon snail. Lewis’ moon snail shells can be up to 13 centimeters across, or about the size of a large grapefruit [2]. The thought of a hermit crab large enough to occupy an entire full size moon snail shell is almost overwhelming. It may be tempting to take these beautiful moon snail shells off of the beach, however for every sea shell you remove from the beach, there is one less shell for a hermit crab to live in.

January 2022: The largest hermit crab I have ever seen, patrolling the margin of a lush eelgrass bed in Campbell River, B.C.

🌎 Distribution 🌎

This hermit has a fairly limited distribution, making it all the more special. It has been spotted as far north as the Gulf of Alaska down to Northern California [3]. Interestingly, this distribution is almost identical to the range of the Lewis’ moon snail, which of course produces the only shell large enough for large adult Black-eyed hermit crabs to live in [4].

Distribution of the Black-eyed hermit crab, Pagurus armatus. Suitable habitat depicted in red.

🏝 Habitat 🏝

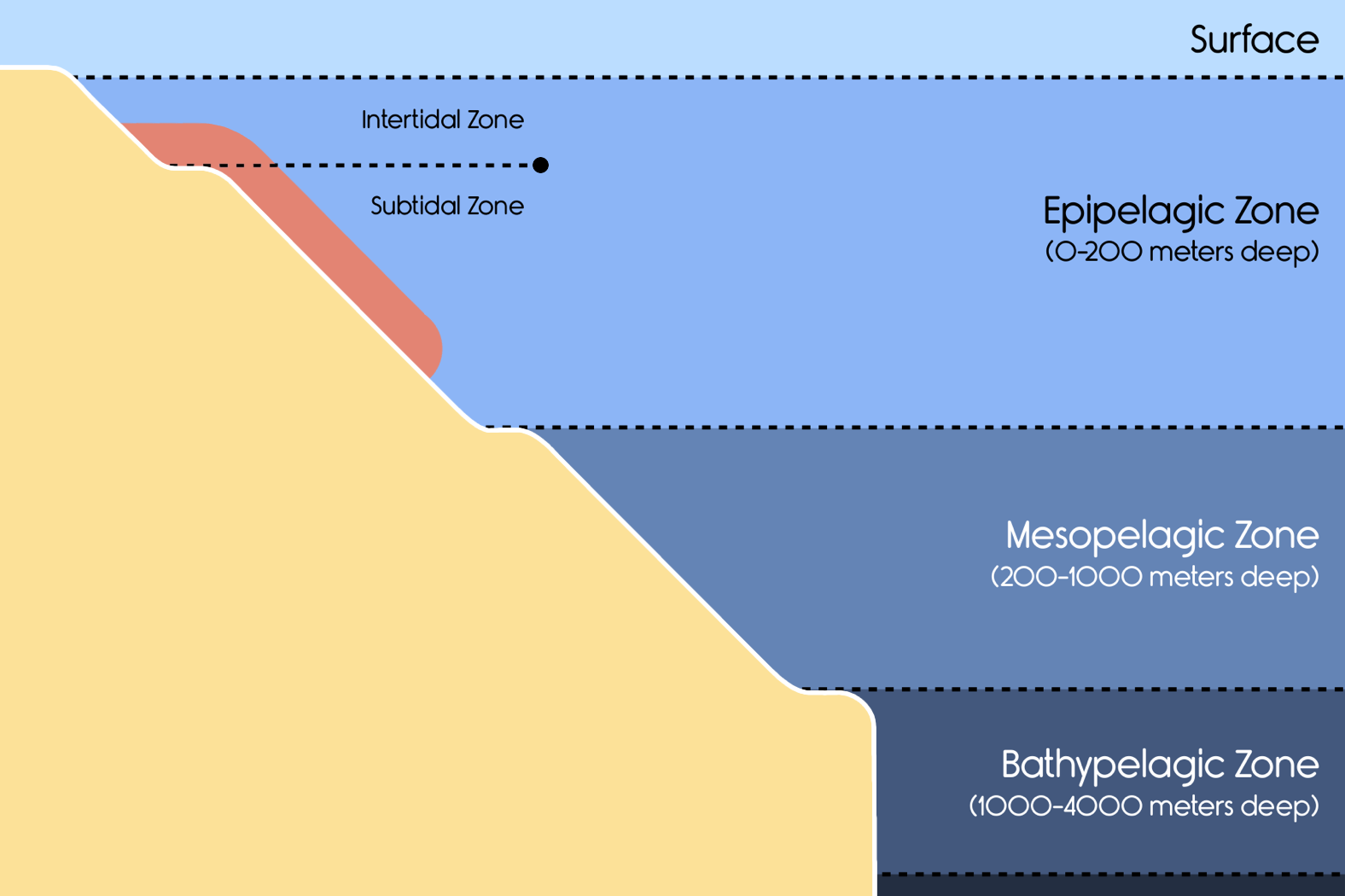

As far as depth is concerned, the Black-eyed hermit is a shallow living species. This creature is among several particularly adorable species (Pacific spiny lumpsucker & Stubby squid) that appear to undergo seasonal migrations to deeper waters in the summer months. Whether this hermit is trying to escape the heat, sunnier weather, or something else entirely has yet to be determined. Rarely, young Black-eyed hermits can be seen in the intertidal zone, and hermits of any age have been documented as far down as 146 meters deep [3].

Depth of suitable habitat for the Black-eyed Hermit crab, Pagurus armatus. Suitable habitat depicted in red. Not to scale.

There are two major marine habitats that the Black-eyed hermit prefers to call home: Eelgrass beds and sea pen gardens. Both of these habitats have sandy/muddy bottoms and plenty of shelter to hide in, whether that be the blades of Zostera eelgrass or the plumes of the Orange sea pen [1]. In either habitat, it would appear that Black-eyed hermits are much more active at night.

May 2016: A young Black-eyed hermit crab hides amongst a garden of Orange sea pens. Can you find them in this picture? Photographed at Clover Point in Victoria, B.C.

🍖 Diet 🍖

Hermit crabs have a diet that is similar to many other local crabs. Much of what they prefer to eat can be scrounged up from the sands of their favourite habitats. Periodically when watching the behaviour of one of these crabs, you will see them ‘taste’ the sand they are sitting on. In some instances, they may be using the taste of the sand to track down morsels of food. This hermit primarily scavenges for dead sea creatures & detritus, using its claws to manipulate chunks of food into manageable bite sized portions.

December 2019: A very young Black-eyed hermit feeds on the moult of a small shrimp. When this species is young, their eyes are not fully black but have yellow highlights at the top. Photographed at Slugget Point in Central Saanich, B.C.

🐚 Life Cycle 🐚

In early spring, Male hermits will begin tracking down females using their antennules and strong sense of smell. Once they have found each other, the male hermit will drag the female around by her shell until she moults. Most crabs cannot mate until the female has moulted, so males make sure to be around for when the moment comes.

Females will carry their eggs around inside of their shell, attached to their tails until they hatch in several months. Once they have hatched, she kicks them out so that they may swim off into the sea to begin their lives [1].

April 2020: A pair of Black-eyed hermit crabs ‘dating’ at the Discovery Passage Aquarium in Campbell River, B.C. These two hermits were being used in educational programming and were returned to the sea soon afterwards.

📚 References 📚

[1] Cowles, D. (2010). Pagurus armatus (Dana, 1851). Invertebrates of the Salish Sea. https://inverts.wallawalla.edu/Arthropoda/Crustacea/Malacostraca/Eumalacostraca/Eucarida/Decapoda/Anomura/Family_Paguridae/Pagurus_armatus.html

[2] Hoehing, D. (1987). Euspira lewisii. Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/site/accounts/information/Euspira_lewisii.html

[3] World Register of Marine Species. (n.d.). Pagurus armatus (Dana, 1851). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=366655#distributions

[4] World Register of Marine Species. (n.d.) Neverita lewisii (A. Gould, 1847). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=718659